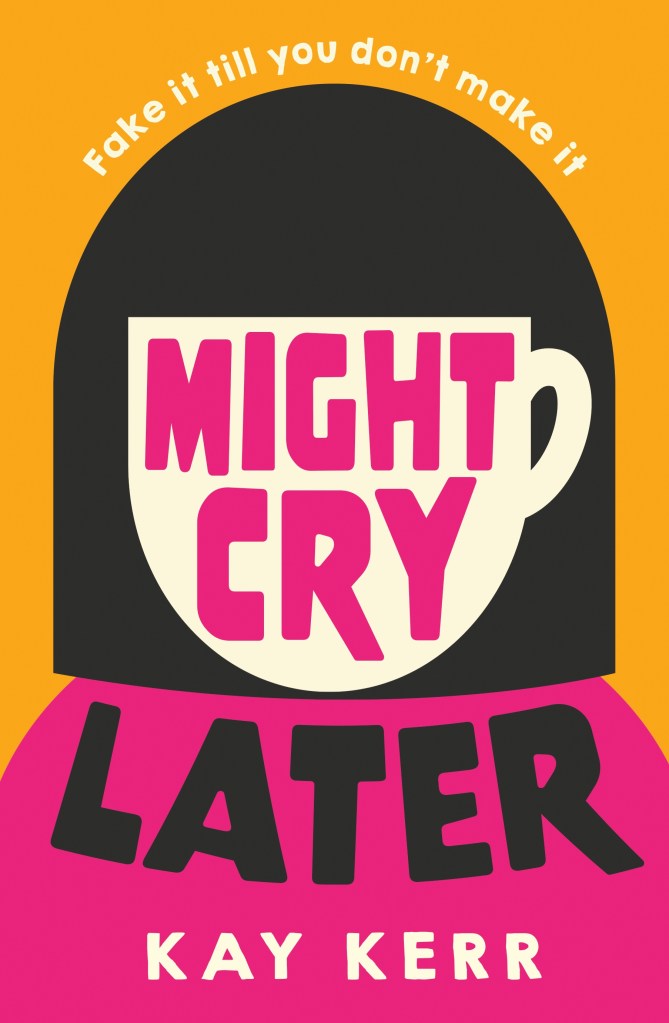

Meet Nora Byrne. Over-thinker, under-achiever, champion vibes-killer.

After spectacularly blowing up her life, twenty-one-year-old Nora Byrne retreats to the family home with little to show for herself but a shiny new autism diagnosis. But it’s hard to process this news under the critical eye of her mother, who already treats her like the black sheep, and the rest of her less-than-understanding family.

Worst of all, it’s the week before Christmas, which means mandatory socialising with the neighbours – including Fran, her childhood best friend, last seen when she broke his heart (again).

Nora’s only goal is to get through the interminable family dinners, awkward Fran encounters and excessive holiday festivities without crying, throwing up, or finding new ways to humiliate herself. But with her track record, it’s not going to be easy…

Q&A

Congratulations on the publication of Might Cry Later! This is your first adult novel, and we notice your main character has grown older with each of your novels. Is this intentional? And have you found that your writing changes when writing adult fiction compared to young adult?

Thank you so much! It has not been a planned ageing up of my protagonists with each book, but I think probably a result of processing my own late autism diagnosis, and the natural timeline of that. I felt there were experiences, feelings, and themes I wanted to explore that needed to be in the adult fiction realm. I don’t differentiate in the writing, I think that would do a disservice to young adults, but the style was naturally different because of what I was writing and the specific perspective of Nora.

You wrote in the Acknowledgments of Might Cry Later that you’ve thought and dreamt of this book for 10 years. Why is this the story you’ve wanted to tell for so long?

There is no conversation I have had more over the past ten years than that of late autism diagnosis—being privileged enough to have published several books with autistic characters has meant I have been lucky enough to connect with countless readers, and without any of that annoying small talk getting in the way, we are always straight into it. The more life stories I heard, the more I started to feel out the through-lines, the similarities (and the differences). It has been endlessly interesting to me to compare notes with other autistic people. I wanted this novel to be one story that reflected what that experience can be like.

You have spoken about your own experience with receiving your autism diagnosis at 26, and we know many neurodivergent women are identified as adults. Was there any particular aspect of that journey that you wanted to highlight with Nora’s story?

There were some aspects of the experience that I had truly never read before, but have talked a lot about with other people diagnosed later in life. Things like burnout, alcohol as a masking tool and coping mechanism, auditory processing issues, maladaptive daydreaming, alexithymia, misdiagnosis, and the feeling of being thrown back into old memories, almost reliving them as a way of processing them through this new lens. That’s not a definitive list, nor is it diagnostic criteria, more that there is just a lot of overlap of experiences, and there is specificity to the emotions that go with so much of it.

We found the portrayal of Nora’s autistic burnout really emotional to read, in the sense that it feels very bone-deep and overwhelming, which we imagine is very true to the experience. If it was hard to read, it probably was hard to write as well at times. How did you approach depicting those emotions?

I think part of why it took me so long to write this book is that I needed distance from my own deepest experiences of burnout, to have some perspective and greater understanding of how a person can get there, and how they might go about getting out. So, I started writing this novel from that point of view, but then life had its own plans and by the time I was editing the novel I was back in burnout, for totally different life reasons than Nora, but being there again really put me in the thick of it, and I feel allowed me to do something creative with all of that struggle. I definitely couldn’t have written a first draft in that state, though.

We’d love to have an in-depth conversation about each of Nora’s family members, they’re all that nuanced! We’ll restrain ourselves to two questions though.

Ha! Look, I had a lot of fun armchair-diagnosing them, so I hope you did, too.

Nora’s sister, Olivia, said at one point that everyone in their family is in pain, they are just terrible at talking about it. Can you tell us about how you came up with this family dynamic?

I came at this through the lens of neurodiversity—I think often a late diagnosis can be treated as this random, isolated thing within a family unit, but that is very much not always the case. And so, I wanted to explore the different ways this showed up in this one specific family. For Olivia, I wanted to challenge I guess the archetype and strict parameters of ‘eldest daughter who has it all together’, and for Nora to start to understand that that was a box she had put her sister in, that was limiting for them both. I think Olivia has put a lot of physical distance between her and her family because she struggled with the roles they had all been assigned, and also the additional mental and emotional load of becoming a mother has meant she is no longer able to fulfill that role. So, through limitations on her own capacity, she is having to shed a bit of that perfectionist image, and it is making her question the roles everyone else is playing as well.

Nora’s mother, Elsie, is really prickly and would have been really easy to cast as a villain. However, as the story goes, Nora and the readers gain some more insight into her as a person. How did you approach writing her character?

Elsie was one of the very first pieces of this story—her dynamic with Nora—because it is one I have seen play out so many times. I started from a real place of frustration and wanting to understand this kind of mother-daughter relationship dynamic, and I feel I really gained perspective through the process of writing Elsie. I spoke to older neurodivergent women about the expectations of girls and women in their generations, about their experiences of motherhood, about the struggles of not gaining this understanding of themselves until much later in life. It made me feel grateful for my own diagnosis in my 20s, which no longer feels all that late in the scheme of things.

We’d love to chat about the impact of Nora’s social communication style and, later, burnout on her friendships with Fran and Cleo. How do you approach writing both of these dynamics?

I think with Cleo, I really wanted to play out the natural consequences of Nora’s actions on their friendship to an endpoint, because regardless of any diagnosis, how you treat a person impacts them, and Nora really does treat Cleo quite poorly at times. I wanted that to be honest, a little brutal, and ultimately understandable on both sides. I have been nervous about how some of Nora’s trickiest moments are going to be read, particularly by non-autistic people, because the last thing I would want would be for her characterization to be reduced to autism=bad person, or bad friend. To me, it is all about the value of having this self-knowledge.

I had very different plans for Fran and Nora’s relationship, but then I spent so much time with them and I completely changed my view. That is as much as I can say in a non-spoiler way. I just love them both.

We love this quote: “It is strange that it is called unmasking at all, when the supposed true self waiting to be revealed has not yet been formed. Unmasking, then, is not a neat end-point, but a recommendation of where and how to start – a slow process, trial and error, a becoming of Nora, rather than a finding of her.” Can you tell us a bit more about this, particularly in relation to Nora’s story?

This is something, again, I was thinking about a lot. We talk about ‘unmasking’ as this neat and tidy thing, as though once you have this new knowledge about yourself, you can simply remove the false version and the real version is going to be hiding underneath. But the reality is, when you spend a lifetime looking outwards to try and figure out what is acceptable ‘normal human behaviour’ and what is not, it can be really confronting and hard to face that you don’t necessarily even know yourself at all. You’ve been taught again and again, in a million different ways, not to trust your own instincts and perception, so learning to do this as an adult can be very difficult. It can also be incredibly isolating, so I wanted Nora to be somewhat of a friend, or a guide (even if she is a guide of what not to do) for people who are facing what can feel like an insurmountable challenge.

Might Cry Later is out now through Pan Macmillan Australia

Support the Show

Has Novel Feelings entertained you, or taught you something? Show your support with a once-off donation by buying us a coffee. All proceeds go towards making the show stronger and more sustainable for the future.

We record our podcast on Wurundjeri Land, which is home to both of us in Naarm/Melbourne. We also acknowledge the role of storytelling in First Nations communities. Always was, always will be Aboriginal Land.